Chapter 15 from All the People

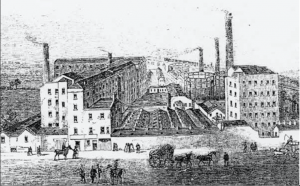

There was a sound of thunder that emanated from the adjoining room. Each blast was louder than the Chorlton Mill at full throttle, but Richard Birley was not in the mill. He had been summoned to the family home, Broom House in Weaste, where he had been required to wait alone for over one half-hour while his uncle, clearly in a state of extreme dudgeon, appeared to be demolishing his furniture. Richard flinched at each new strike as if his own head was the target.

By good chance, he had been provided with a large crystal-cut glass of brandy, a necessary placation that he had finished within seconds when his uncle’s servant tendered another, leaving behind the matching Stourbridge decanter. If he had to dally, doing nothing but listen to his uncle’s rage, then he would recline in his uncle’s chair and seek to enjoy the peculiar experience.

Trying hard to offset the usual feeling of uneasiness when in Broom House, he drank his second brandy in one, swift draught. Richard was particularly unnerved when in this room, where the walls were covered from floor to ceiling with pictorial compositions of his family through many generations. Only the centrepiece, the large painting of his uncle when in his younger days, was worthy of attention. Elsewhere, he spied only primitive portraits of his and his host’s smug ancestors, each engaged in a battle for space with corpselike horses and dogs in the fashion of poor George Stubbs imitators, buried within dull frames of wood veneer. As his eyes, already glazing with the effects of the alcohol, stared back at the faces peering at him from the wall, he noticed that one was moving stealthily towards him. He sat up, startled, becoming only slowly aware that his uncle had entered the room and that the crashing sounds had ceased.

“Now, at last, let us get to business,” the older man demanded, as Richard escaped his inner contemplation. Hugh Birley, still standing, looked overly heated and it was unclear whether the argument that had raged in the other room had been won or lost. Richard vacated his uncle’s seat, asked after his uncle’s health and wondered out loud if the Anti-Corn Law League was causing him undue irritation. He was delighted that the words came quickly enough to obscure the fact that he had been sitting where he was not supposed: “Anti-Corn Law League?” his uncle shouted back before flopping into the just-vacated chair. Richard found another place to sit, after taking the Staffordshire crystal decanter and his half-full glass. “I disagree with their sentiments, but they are nothing compared to this!” Birley exclaimed, throwing a newspaper into Richard’s lap. His nephew glanced its way and took it with his free hand as he looked for a table on which to place his newly-emptied glass.

Hugh Hornby Birley shouted with a sense of rage felt keenly at a prospective loss of control in the nation. His eyes darted around the room as if seeking new objects to throw. “We are losing control, Richard! I hear rumours of every kind of violence proposed by the lower classes in this town. Yes, here in Manchester itself! And, as if matters could not be worse, we have been ordered to keep the mills and factories closed this coming Monday.” Richard looked blank, although his uncle assumed that to be his normal expression. “There is to be a ‘holiday’ from work! To facilitate nothing less than a workers’ assembly on Kersal Moor! A workers’ assembly! Forced to close for a workers’ assembly! To think that we should ever bow to the working classes’ desire for a day’s closure! The fault lies with the Northern Star! The Northern Star! Do you know how often I have seen that assembly of lies being read in our own Chorlton Mill?” He examined his nephew’s face for any recognition. “Do you even know what the Star is? Richard, have you seen it before?” He looked quizzically at his nephew.

So many questions, his nephew thought. How could he be expected to memorize so many questions? Richard nodded affirmatively, rather than risk a vocal response that was guaranteed to be criticised whatever he said, allowing his uncle, whose questions were likely rhetorical, to continue: “Well, good that you do. Best to know one’s enemies. I have the copies of that scandalous sheet confiscated whenever we find them, but our workers simply walk outside to read it, those that are able. There are always more copies to be had than we destroy. Those that cannot read, well, they listen to those that are able to tell them how this Irishman, Bronterre O’Brien, or that Irishman, Feargus O’Connor, who publishes the paper, or the Reverend Stephens or some other unsavoury individual rants in print concerning the right to the vote or shorter hours or higher pay or an end to the Poor Law or whatever may serve their purpose on any given day.”

He inhaled deeply: “We all know what serves their purpose: power and influence! Such rabble-rousers adore the promise of power and they care not a cotton thread about how they obtain it or the dangers they cause or the lies they tell. Does Feargus O’Connor, the land-owning Irishman who owns the paper, have sympathy for the poor of this land? Pah! Does he see the state of his own country folk in this town?” He looked fiercely at his nephew, who shook his head in a negative fashion, relieved that his head had moved in the correct manner. “What has he ever done to improve their lot compared to you and me who provide the work and aid their survival? Where would his people be without the wages that we pay them? Back in Ireland, if I had my way, I can tell you!”

His nephew nodded again, as vigorously as he felt able. A third brandy had left him feeling rather sleepy, hardly able to keep up with his uncle’s heady direction of discourse. The latter rose again, took the Northern Star from Richard’s weak grasp and held it high, with both hands. “This is our danger! Its lies and intrigues befuddle the heads of its readers who then carry on the deception to the masses that cannot read. Through this sheet of fabrications, they believe they have rights! Rights! A day off to march in Kersal Moor will be just the beginning, Richard. We need to prepare for the fight to come and you must rally the men in the town, rally the Chamber of Commerce! Make them understand the dangers of workers filled with ideas well above their station! We must restore the natural order!”

Richard Birley squinted at this demand. A fourth brandy was about to be consumed and he nodded in whatever way would appease his uncle, who now appeared, at least to Richard’s eyes, quite unbalanced. To regain a degree of equanimity, Richard gazed again at the paintings of his family that hung on the wall, where every canvas was held perfectly secure in their wooden caskets, a feeling to which he could only aspire.

___

There was a painting in Mr Birley’s office, where she had once been sent for punishment: a huge canvas held within an ornate, golden frame that seemed to cover the whole wall. It displayed a bright, yellow sun shining brightly over wide fields of the greenest grass with animals, cows, goats and sheep, resting under clear skies. It had held her gaze that day and, because it transfixed her sight, Mr Birley had thought her inattentive and she had been hit about the body by the ogre that had taken her to him.

How she wished that the scene before her resembled that landscape. From where Mary had been sleeping, as the weak sun peaked through the clouds the horizon remained imperceptible. Darkness filled the sky and there was not a blade of grass to be seen amongst the mills and factories. She had been told how vast swathes of green had been obliterated to build the wealth-creating mills. Perhaps the dark sight was but a nightmare and Mary rubbed her eyes to certify she was not asleep.

When a ray from the sun hit the ceiling, her eyes veered to the left to check if her father was yet awake. She laughed at the instinctive movement and her body relaxed, for Michael Burns was not in the room. Two years had passed since she had left his house, never to return, but she could not help recalling, each day, the burden that she had endured for so long. Now, every time she awoke, pangs of fear were recalled, and she instinctively looked in the direction where he had once lain. In the room that she now shared with six others, including her sister, Lizzie, she now slept in a bed, not on the floor and, on most days, had no one to wake but herself.

The memory of the painting faded along with the hesitant sunshine that hid behind clouds and smoke, but she cared little for the gloom outside, for this day would be bright no matter whether the sun shone or not.

She began to wake the others, her fellow pilgrims that day. Within twenty minutes, Mary and her fellow seekers after enlightenment had dressed, loaded bags with food and drink and were already walking outside, mingling with many others headed in the same direction.

With determination etched on each countenance, their pace gradually quickened to ensure that they would arrive at their destination early to secure an advantageous position. The centre of Manchester was already crowded as they passed through. Mary wondered how her employer must detest the freedom that they had been given, even for just one day. For some, it may be a day’s holiday from work, but, for others, many others, they had no jobs to return to. She had feared she would be amongst that category when The Northern Star and its recalcitrant reader were presented for Mr Mainthorpe’s judicious review and likely punishment. She had expected a beating and the street, but Mr Mainthorpe had taken much time informing her how the recession was a disease that was spreading from the old to the young, from the higher-waged to the lower-waged. She was sixteen, but there were younger girls, he had said, with nimbler feet and smaller hands, happy to grasp fewer coins when the weekly wages were paid. He had a valid reason to dismiss her, he stressed: the reading of The Northern Star, the newspaper most hated by his boss, Mr Birley, because it supported the unjustified yearnings of working people. Yet, the beating never came, and Mr Mainthorpe had not dismissed her, but merely scolded her, calling her ‘rebellious’ and advising her that the Star must never be brought into the mill again. “Next time,” he had said, shaking a finger in the air, all the while peeking distractedly through the window into the thunderous streets outside, “would be the last time.”

She had gloried in the adjective that Mr Mainthorpe has applied to her and the ‘rebellious’ young lady now held another copy of the journal in her hands. She waved it at each mill they passed like a flag of war as any thoughts about the fears for her employment were placed on hold while the pilgrimage to Kersal Moor continued. If she was fortunate, she would see the Irishman that was almost the cause of her dismissal and the fount of her hopes.

Mary Burns was amongst her friends from the streets where she lived, young men and women that yearned for higher wages or just for work, housing and enough to eat. They walked with her in the early hours into Smithfield, the heart of Manchester, almost lost amongst the thousands that were congregating, voices raised, not in anger but in anticipation, their shouts ringing through the streets and their banners raised high in the air.

From Smithfield, the multitudes assembled and then marched together on to Kersal Moor, four miles to the north west of the Town, on a cold, late September morning, warmed by the briskness of their walking, waving their flags high and shouting slogans of support for their immediate aims: the People’s Charter and an end to the Poor Laws. It was unusual to be amongst so many others with similar beliefs, a solidarity of purpose that she had never heard so vocalised, an exultation that she had been told could only be experienced in a church. The Chorlton Mill had allowed her one diversion during those long hours of work and fear: the daily reading of the Northern Star. It provided her with information unlike anything before, a guide to the truth and to the actions taken by others that believed as she did and suffered in the way she suffered. Many of the men that wrote those words would be speaking at Kersal Moor.

Those grasslands had become a temporary home to a vast gathering that Mary and her friends joined well before midday as they ran on to the Moor, dancing when their feet touched the dew-touched grass, as young people will, when freed from daily burdens. The crowd was rapidly growing. Working people from across the north-west of England were gathering in their thousands: families with their children, away from the relentlessness of existence, released to spend time amongst the marching bands, trades unions and associations on a day that had been made a holiday. Mary shouted as she danced: “A holiday!” It was as if an Easter Parade had been imprisoned in a large box, where it had lain dormant from early Spring and throughout the Summer, but escaped into the early Autumn, twice as exuberant, hungry with enthusiasm, determined to make a spectacle amidst the sounds of laughter, the singing of psalms, the beating of drums and the expectation of inspirational speeches.

Such elevated spirits rose throughout the morning in anticipation of the speakers who, at noon, began to assemble at the hustings. Mary spied no women speakers and considered their absence. Did she not read to the men in the mill? Was there a custom amongst working people for women just to support, not lead? She raised the subject with her friends: “England may have a Queen, but few men fight for the female vote,” said one, while another interjected: “Henry Hunt did! I remember my mother saying so, but she also said that while the People’s Charter was for men and women, ‘universal’ suffrage was for men only.” Another ventured: “Surely those fighting for the People’s Charter believe that the proper place for women is in the home!” One of the men nearby joined in: “Surely, you ladies would be better off not having to work? Safe at home with children is where you should be!” Mary remained silent despite a growing unease at such solid affirmations, made by men to assert their position in society just as the owners of property asserted their sole rights to the vote.

While her mind was contemplating such dilemmas, she was bustled from her thoughts by a group of rowdy men, whose banners proclaimed them members of the Boot and Shoemakers Association. They had been marching, shouting and drinking all morning and stopped by Mary’s friends to strike up hearty conversations. Within the fifteen-acre amphitheatre, erected to allow everyone to see the procession, they all were silent as the trumpeters appeared on horseback, followed by each of the worker associations. When the Boot and Shoemakers Association passed by, with their banners and flags held high, the men close by Mary cheered loudly at their representatives. Not far behind was a huge portrait of Henry Hunt, the hero of Peterloo, carried by two men. Underneath his picture was written: ‘the man who never deserted the cause’ and, on the back it read: ‘Equality, the first law of nature’. Mary cheered as loud as she could for the man who had risked his life to give all men, and possibly all women, the vote.

The procession travelled around the grounds for another thirty minutes, eventually winding its way to the head of Kersal Moor, where the speeches were to be made. Banners alongside showed the six demands of the People’s Charter. One by one, six men, standing on the stage, called out the demands:

“Votes for all men over 21”, shouted the first to great cheers.

“We demand a secret Ballot” called the second to similar acclaim.

“No Property Qualifications,” screamed the third, the applause and cheers becoming louder.

“We demand Payment of Members of Parliament so that all can stand,” shouted the fourth, a rather small man who could hear, amongst the cheers, shouts of “You should stand!” to which he smiled, clearly having heard such eloquence before.

The fifth man, standing taller, shouted “Equal Constituencies”, to shouts and some laughter that carried over from the fourth.

At last, the sixth man jumped up: “Annual Ballots”, he called out and the whole congregation rose to applaud for some minutes before the small man reappeared to quieten them.

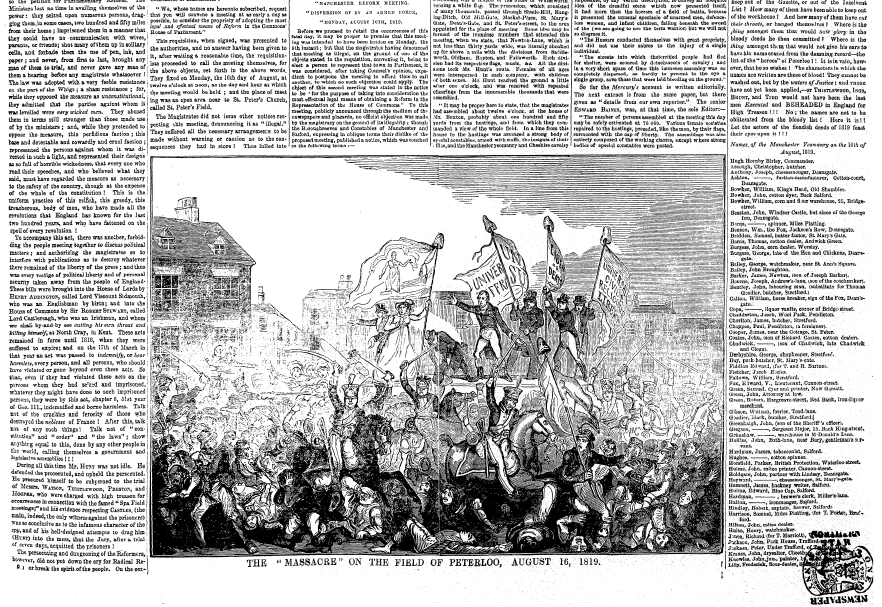

When they had finished and moved off the stage, the vans holding the banners and the leaders of the procession passed by again. It was now one o’clock and the amphitheatre appeared to be bursting, so many were present. One of the shoemakers, standing close to Mary, shouted above the noise: “There are over three hundred thousand people here this day! No one can ignore us now!” Although there was no way of knowing, Mary considered that she was part of an historic event, one she would never forget. She would not be alone in those thoughts, she believed. Others would remember this day, she knew, as she spied a large group of soldiers, marked out by their colourful uniforms. Two were on horseback, gesticulating to those on foot. They appeared ready to march forward at any time. Mary’s heart leapt. She could only hope that the stories from nineteen years before were not to be repeated.

Mary turned in time to see, in the far distance, the first speaker clambering on to the stage. She was told that he was Mr John Fielden, the Member of Parliament for the radical town of Oldham and a mill owner. She could just hear him speak, with some passion judging by his gesticulations. She heard him shout, to many, many cheers, that ‘universal suffrage enshrined our basic rights’ and would soon be won from the landed rulers of the House of Commons. Then the wind changed direction and his voice was silenced for those near to where Mary stood, but there were others that passed along his words like a game of whispers. She was told that Fielden had “damned the wealthy for denying the poor the vote just because they were poor and unintelligent” and that he had said: “Yes, these people were poor”, but that should be no bar and as for intelligence, they had far more than those in Parliament.” This received huge applause, even from those who had heard not one word of his speech, because cheering is infectious.

When he sat down, there was so much wild acclaim that Mary would later affirm that she felt the ground shake. Many more speeches followed, and more resolutions were passed before the man Mary had come to see, Feargus O’Connor, appeared. The Northern Star was full of his fiery words and she could feel a sense of the man just from reading them, but now she would see him and, if the elements conspired in her favour, she might hear him speak! She feared that her ears would burst with the strain of trying to hear him but, once the cheers died down after he had risen, there was silence amongst all those watching, each keen to hear. The big man spoke in a loud voice that echoed throughout the amphitheatre, when the wind died a little on this very windy day. O’Connor waited for calm and Mary saw him standing silently until his words, or those that she could hear, rode the strong northerly that carried them, or most of them, to all corners of the grounds. She heard him say:

“The universal suffrage must be won.”

If she heard nothing else, that would have sufficed, but he continued for much longer, one of his lengthy speeches that he was fond of making, the sound of his voice captivating those near to him and himself, some were known to state. For those farther away, like Mary, the hearing was partial and dependent on the strength and direction of the gale that seemed to be for ever changing its mind and direction.

When Feargus finally sat down, the people cheered and cheered and threw their hats into the air, whether they had heard his words or not. Mary stood silently as she allowed the words that she had received to take root inside her. When, in seconds, they had been embedded, she released the tensions of her short lifetime into the air of Kersal Moor: the hunger, the sharp words and sharper fists of her father, the early mornings and later nights, the lingering hands and frightening fists of the overlookers, demanding a supplication that she would never give or the heady blows that resulted, they were all expelled by the loudest of shouts she could manage, screams over which she had no control. She saw the same reaction from everyone close to her. It was an outflow of feelings to one man’s words, a man she did not know except through his writing, but whose phrases unlocked suppressed emotions, opening a sealed door that could never be closed again.

After more resolutions were concluded and the votes counted, the rain began to fall. It dropped heavily, but few even noticed that they were wet and less seemed to care. After John Fielden rose to thank all those who had come that day and gave special thanks to Feargus O’Connor, a cry rang out: “Three cheers for Feargus” and all cheered as the thousands upon thousands began to make their way home, the Easter Parade at an end, but not eager to return inside its box.

Those that were more ardent in their desire to slip the lid and lock it shut, the band of soldiers, remained for some time while the massed crowds departed. Major General Sir Charles J Napier, appointed to the Northern District just a few months earlier by the Home Secretary, Lord John Russell, was content that there were no violent disturbances. He considered that it had been a day for incautious words but that was all. He commanded Colonel Wemyss, one of his best officers, who he had decided to retain in Manchester, to disperse his troops. While there were only one hundred or so soldiers at Kersal Moor, Napier had ensured that they now had over two thousand stationed in Manchester: a town that he considered to be the centre of a likely insurrection against the State.

It is ironic that deep beneath St Peter’s Square in the heart of Manchester lies the Birley family crypt. Burrow beneath the streets where St Peter’s Church once stood and you will find the tombs where Hugh Hornby Birley was buried on 8 August 1845, just eight days before the 26th anniversary of Peterloo. By that time, it is doubtful that anyone congregated outside his mill or home, but the ghosts of St Peter’s Field could jeer at his corpse for an eternity.’

It is ironic that deep beneath St Peter’s Square in the heart of Manchester lies the Birley family crypt. Burrow beneath the streets where St Peter’s Church once stood and you will find the tombs where Hugh Hornby Birley was buried on 8 August 1845, just eight days before the 26th anniversary of Peterloo. By that time, it is doubtful that anyone congregated outside his mill or home, but the ghosts of St Peter’s Field could jeer at his corpse for an eternity.’