PFI was Government outsourcing at its worst as the Independent has uncovered. There is a saying “There are no free lunches” but politicians like to pretend that there are.

PFI was a scheme to bring forward capital spending for hospitals, schools, care homes and others areas of under-funded public utilities without showing it in spending profiles – without being honest and transparent with the public about what it was doing.

Ally this to the cozy relationship between certain politicians and those in the building and construction industry and the inability of civil servants to really understand enough about the risks to dissuade politicians and the recipe was in place.

What we have is a burden on our public sector that will not impact the politicians that made the decisions but will have grave (in some cases literally) consequences for those who will be unable to be provided with the care they need as costs in our public sector rise over the next few decades as the bills are paid.

Back in 1998, when I was a Trustee / Governor at a local school in North London, I identified that the school needed to be rebuilt. It was crumbling, had asbestos, its electrical wiring was unsafe, roofs were collapsing and let in vast amounts of rain water and the school had to make use of temporary facilities that were installed 30 years before. There was a real danger that the school would be closed at some time in the future unless radical steps were taken and the only answer was to rebuild.

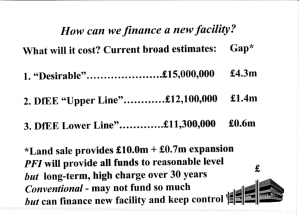

I made a presentation to the Board of Governors in 1998 where I proposed that, while PFI was an option being actively touted by Government as a panacea, we should not touch it. In Powerpoint slides, printed and shown on an overhead projector (we could not afford the computer equipment) I tried to persuade reluctant but well-meaning local people to reject the obvious answer because of “long-term high charge over 30 years” and loss of control over our own assets. The slide shown 17 years ago is below:

The school, now Ashmole Academy in Barnet was built without PFI – although it took until 2004 to see it through. Eleven years’ later, the school (where I was Chair for 12 years from 2002 until 2014) remains in excellent condition and is an excellent school – one of the best in England.

When this Government began its enquiry into school buildings a few years’ ago, it commissioned Sebastian James and his team that produced the James Report.

This report, to which a few of us from the board at Ashmole made representations and met with members of the Report team prior to publication, did not condemn PFI but simply said:

Private Finance Initiative

A procurement route established in 1995, and more widely adopted since 1997. It is an important route for much Government spending on assets as it transfers significant risks to the private sector. PFI requires private sector consortia to raise private finance to fund a project, which must involve investment in assets, and the long-term delivery of services to the public sector.

As a result, PFI was allowed to continue on the basis that it meant to provide a “transfer of risks to the private sector”. For this transfer (which is really nonsense as the transfer was merely to get public sector spending off the books and into the books of the companies), the construction and service companies were handsomely compensated.

Not only that, but local and national public sectors were completely overwhelmed by the prospect of architectural excellence rather than practical building and this resulted in grandiose schemes that impress architects and win awards but ended up being hard to maintain, costly to build and a long-term drain on finances.

The lessor, now the School or the local authority is then stuck with a long-term agreement which it has to pay – at costs which are far greater than those which a Government could have loaned the money at – just to get costs off the books so no-one would notice that the financial burden was excessive while the new facilities were being built.

As to the risk being transferred, at Ashmole, we decided to take on such risk and then make sure that we had good contractors, good architects, good project management overseen by knowledgeable Board directors / trustees and good contracts in place. The risk was normal – it was on the suppliers not the school as we were the customers. The risk issue is nonsense.

The James Report is now forgotten but should have been a reminder that PFI was a major accident waiting to happen.

The Independent’s Report highlights not just the crippling costs of PFI but also the problems that are met when government (local and national) become swept away by those in the private sector who promise a free lunch and by their own lack of transparency and inability to understand business.

We entrust Government with much of our future but, while we condemn those that allowed PFI to take place in such a shambolic way, we should bear in mind that we may be expecting far too much in an area of greatest risk – the place where public and private sector meet. Knowledge and capability on either side are varied but neither really “gets” the other. This is why banking crises will always appear from time to time and why outsourcing of public sector often delivers much less than “expected”.

The place where public and private sector meet is a dangerous one and is less well understood than the specific sectors themselves. However, one way that such disasters as PFI could be reduced is through transparency – it was the desire to keep costs “off the books” that took us into PFI when extra expenditure on the public sector financed by low-costs Treasuries would have been a far better investment.

However, the pressure to falsely account was made by the pressure put on politicians by keeping government spending down even in the face of greatest need. It is why, even today, the NHS funding row is all about showing how the £8bn will be afforded in years to come when we all really know that we have very little idea what the UK’s finances will look like in three to five years. Good management of finances does not mean we can possibly be that accurate (no company really believes it knows how it will be doing beyond twelve months and beyond that, forecasts are but guides based on spreadsheets – the same is true of economies but with thousands more indeterminate variables).

So, PFI and similar comes from our desire to lie to ourselves and for politicians to lie to a public that is implicit in the lie.

We need to educate ourselves to reality by being more transparent.